Contributed by Leith Johnson, Processing Archivist

In April, 2010, the Helga J. Ingraham Memorial Library acquired a small journal, about six inches by four inches, that has “Cap. Phinehas Baldwins Book” written on the cover. Inside are entries that document various activities of what seems to be a busy Litchfield resident: goods are bought and sold, services are provided, bridges are inspected, letters are written about people at the poor house, a woman and her family are warned away from town. The earliest entry is from 1784 and the last is from 1829. All in all, a very informative little book and a significant addition to the library’s collections.

As project archivist working under the CLIR grant, it’s my job to process this journal and add it to the Archon database of finding aids to the archival materials. Typically, I conduct research on each collection in order to help the researcher place the materials in a broader historical context. In the case of Capt. Phineas Baldwin’s journal, I ended up doing quite a bit of detective work, as it turned out that it was not what it at first seemed.

I started my research by skimming the journal to get a general sense of what it contained. One thing immediately struck me: there are two different sets of handwriting, suggesting that two different individuals had used the book. Aside from the name written on the cover, I could find no inscription actually giving the name of either writer. I then read several pages of information on Phineas Baldwin of Litchfield provided by the bookseller from whom the library had acquired the journal. The report stated that Baldwin was “magistrate, surveyor, bridge builder.” In the 1780s, because of his Loyalist sympathies during the American Revolution, Baldwin and his wife, Sarah Landon Baldwin, moved to Canada. He died there sometime in the 1840s.

Immediately, there were contradictions between the bookseller’s research and what I could observe in the book. Besides the handwriting of two individuals, the journal contained entries written in the second hand that referred to the estate of Phineas Baldwin with the dates of 1816 and 1817. Obviously, a man who died in 1817 could not be alive in Canada until the 1840s. A closer inspection of the entries showed that they all relate to Litchfield, providing more evidence that the writers of the journal never were in Canada. Lastly, the first name found on the cover is spelled “Phinehas.” If the book belonged to Phineas Baldwin of Litchfield and Canada, as indicated in the sources in the report, why would he misspell his own name? And if the book did not belong to the Phineas Baldwin of Litchfield and Canada, who did it belong to?

A good source for learning who lived in Litchfield in the late 1700s and early 1800s is A Genealogical Register of the Inhabitants of the Town of Litchfield, Conn. written by George C. Woodruff and published in 1900. I checked the listings under Baldwin and discovered something interesting: at one time, there were two Phineas Baldwins living in Litchfield. One was the son of David Baldwin and was married to Sarah Landon—he was our Canadian acquaintance. The other Phineas Baldwin was the son of a different David Baldwin and was married to Mary Cook. I then checked another good source for who lived in Litchfield in the 1800s: Litchfield and Morris Inscriptions transcribed by Charles Thomas Payne and published in 1905. This book contained a gravestone inscription in the East Burying Ground: “In memory of Capt. Phineas Baldwin who died July 27, 1817, in the 70 year of his age.” Next to it is the gravestone of his wife, Mary.

This was a good match, but I wanted to know more about my new friend Capt. Baldwin. I checked the library’s genealogy and research files, but did not find anything beyond what I already knew. So, I did some Google searching. Unfortunately, there was not a lot to find, but I did come across one very useful source. In The Baldwin Genealogy from 1500 to 1881, available at the Internet Archives Web site, there is a listing for Phineas that indicates that his wife died just one month after he did and that they had no children. Further, there are details about his will. Although there is no mention of an executor, I learned that he named his wife, children of several of his siblings, and the children of his wife’s cousin Nathan Cook as beneficiaries. This last bit is significant, because there is also an entry in the journal pertaining to Phineas Baldwin’s estate and the children of Nathan Cook.

Although I was satisfied that I had established that Capt. Baldwin, the life-long Litchfield resident, was one writer of the book, I still did not know the identity of the other. Again, the journal provided an important clue, an entry about an advertisement regarding claims against an estate with the dates of July and August 1817. It had the wording of advertisements placed by executors and administrators of estates that I had seen published many times before, and I knew that the name of the executor would be in the advertisement. The next question was, in what newspaper would the executor have placed in the advertisement? In the early 1800s, several newspapers were published in Litchfield and there was not necessarily a paper published in each year. I surveyed the library’s holdings and checked with Linda Hocking, and we determined that 1817 was a year in which there was no Litchfield newspaper. It seemed logical that the Hartford Courant may have been chosen; at least, I had ready access to its complete publication run online and it would be easy enough to check. I got lucky. On Aug. 12, 1817, in what was then called the Connecticut Courant, there was an advertisement placed by Capt. Phineas Baldwin’s executor, Reuben Webster. It seemed I had found my second writer. But who was Reuben Webster?

I consulted several of the library’s books on Litchfield history and genealogy files and found out that Webster was a storekeeper. More important to me was that he had been active in local affairs. He served in the American Revolutionary War and was a jailer in the late 1790s; constable, 1805; selectman, 1822-1824; grand juror, 1824; and assessor, 1828. That he was a selectman from 1822 to 1824 was of particular importance. In the journal, there are number of entries from 1823 to 1824 regarding activities concerning official town business, such as sending letters to selectmen of other towns, inspecting bridges, sending out notices for town meetings, and so on—just the types of activities in which a selectman would be involved. The dates lined up perfectly.

So, at this point, chances were good that Reuben Webster was the second writer, but I wanted one more piece of evidence: I wanted to see if Webster’s known handwriting matched that in the journal. The library happens to have documents written by Webster, which I easily found by consulting Archon. I retrieved bills he submitted for expenses he incurred as jailer in 1799 and 1800. Matching handwriting can be tricky business, but it was easy to see by putting the bills next to passages in the journal that they could very well have been written by the same person.

With this final piece, I believed I had completed the puzzle. Reuben Webster was the second writer. He was the executor of Capt. Baldwin’s will and the journal contains notations related to Capt. Baldwin’s estate. As executor, Webster would need the book in settling Capt. Baldwin’s estate, which explains how the book came into Webster’s possession. He was a selectman at the same time as the entries that describe the activities of someone involved in town business. Webster’s handwriting strongly resembles the handwriting of the second writer.

Finally, what to make out of the misspelling of Capt. Baldwin’s first name on the cover? That would have been Webster’s minor error. A friend or associate of Capt. Baldwin, which is what Webster presumably was, can be excused by not getting the name exactly right, since “Phinehas” and “Phineas” were both in use.

One last thing about the journal: there are two accounts of washing done in 1822 for Jacob Baker and Henry Cruger. I Googled Jacob Baker and discovered he was a lawyer. On a hunch, I searched for him in The Ledger, the Society’s new database that documents Litchfield Law School students, and, sure enough, he was student at that time. So was Cruger. I wonder if they boarded with Webster or if a member of his household took in washing.

My research on the Capt. Phineas Baldwin and Reuben Webster journal is just one example of the work regularly performed by the staff to describe and process archival materials, accession collections, create exhibitions, and develop and present public programs.

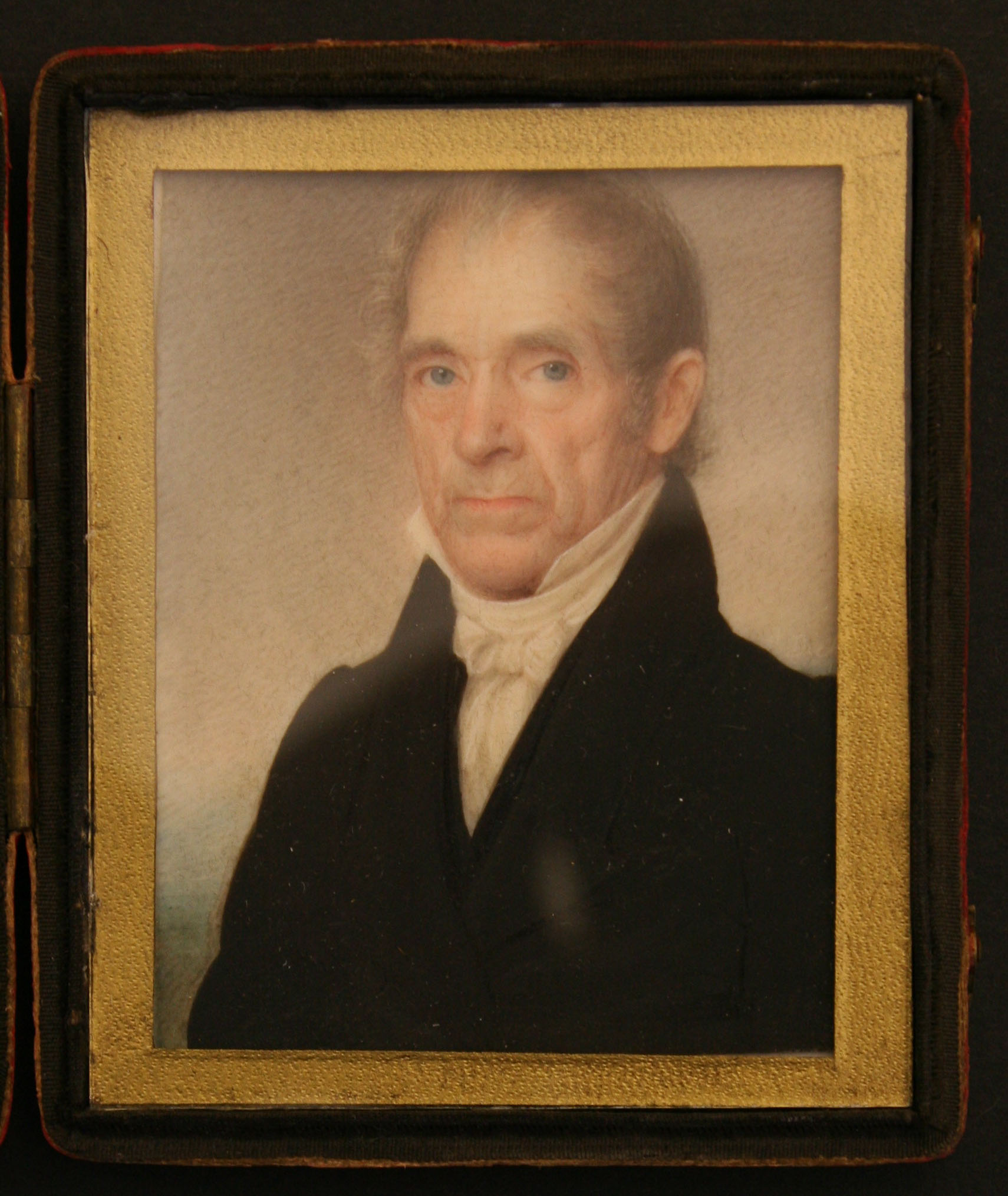

Portrait Miniature, Reuben Webster by Anson Dickinson